Perspective brings you thoughts and insights from Bank experts, focusing on the latest research, trends, and issues facing the economy of the Third District and beyond.

Perhaps it’s the old civil engineer in me and my previous life as a “quant,” but I have found that one of the pleasures of leading a Federal Reserve Bank is the amount of data we have access to. From big broad numbers like GDP and employment growth to more granular figures like auto sales and even restaurant reservations, solid data are crucial to effective policymaking. And in recent years, new sources like mobility data ― which give us (anonymized) information on how much people are traveling and to where ― have only served to more fully inform the Fed’s understanding of a subject as vast and as complex as the U.S. economy.

While headline numbers are important and tell us a lot, I find it particularly crucial to understand how people’s economic realities are playing out on the ground. This has been especially true throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, an unprecedented economic and public health shock that has drastically affected the way Americans live.

And so, since April 2020, the Philadelphia Fed’s Consumer Finance Institute (CFI) has conducted 10 national surveys of Americans about changes in their job status, income levels, and personal financial security. This series of surveys ― the CFI COVID-19 Survey of Consumers ― has provided invaluable information about the way we live now. It has also ― in my view ― furnished us with important lessons as we move into the new year.

I’d like to focus on just two of those lessons right now.

The first is the importance of effective communication and policy design. The U.S. Congress and the Trump and Biden administrations have passed significant tranches of fiscal relief throughout the pandemic, beginning with the CARES Act in spring 2020. That included broad-based measures like relief checks to a majority of households, as well as more targeted programs like eviction moratoriums, student loan payment suspensions, rental assistance, and mortgage forbearance. In some cases, these relief measures were applied automatically; in others, would-be recipients had to apply.

That’s important because our surveys have found persistent gaps in how aware Americans are of programs they could potentially benefit from. For instance, in the third iteration of the survey, fielded in June 2020, fewer than half of respondents reported that they were aware of the major components of the CARES Act and other relief programs. And perversely, those who stood to benefit tended to be less aware: the CFI’s surveys found that lower-earning respondents had generally lower awareness of relief programs than those with higher earnings. Non-White respondents have also persistently lagged in awareness. In July 2021, for example, the CFI found that “one out of nine lower-income or non-White respondents said they did not know enough about [COVID relief] programs to determine whether the aid would help them.”

While headline numbers are important and tell us a lot, I find it particularly crucial to understand how people's economic realities are playing out on the ground.

These gaps have had clear effects; we know that many people who would have qualified for mortgage forbearance never applied for it, for instance, meaning they are at risk of a foreclosure that could have been avoided. Renters encountered similar issues ― more than half of renters surveyed in October 2021 said they needed rental assistance at some point during the pandemic, but 43 percent of them didn’t apply for it because they weren’t sure how to find programs in their area.

That speaks to the importance of effective and creative communication; no matter how well intentioned or designed a relief program may be, it is bound to fail if many who are eligible for it are simply unaware of its existence. Another possibility going forward would be to design more programs so they could take effect automatically. Cumbersome and confusing opt-in provisions often serve only to lock people out of programs that should have been easily accessible.

Another persistent feature of the COVID-19 pandemic has been what I would call disparate improvement, as opposed to disparate impact. That is, as the pandemic has worn on, some segments of Americans have experienced improving economic situations even as others have continued to suffer.

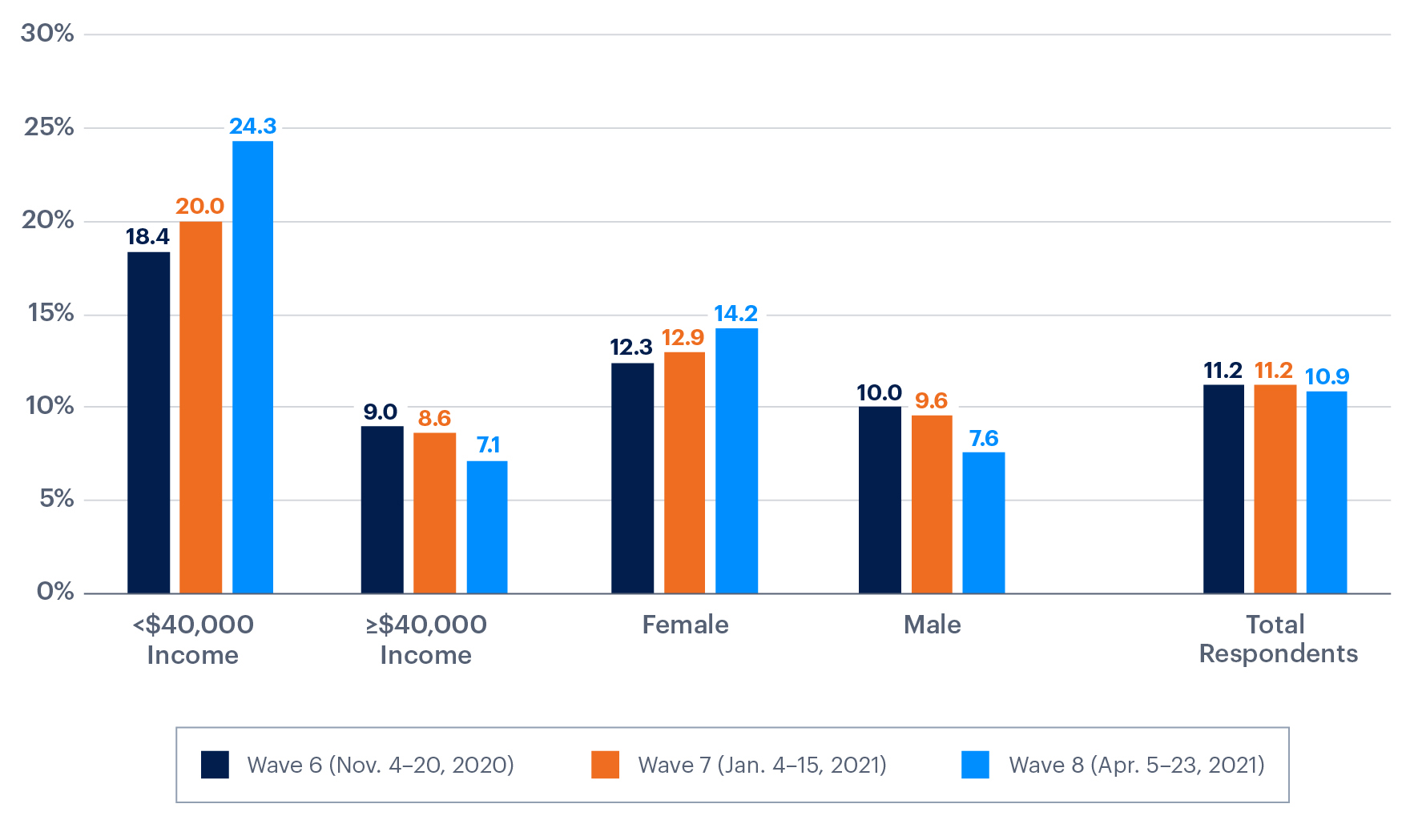

For instance, in April 2021, the percentage of respondents who reported having lost their job was 10.9 percent, relatively flat from November 2020, when reported job loss came in at 11.2 percent of respondents. But that headline number obscures real differences: Two demographic segments showed consistent increases in job loss since November 2020 ― respondents who previously earned less than $40,000 increased from 18.4 percent to 24.3 percent over that period, while female respondents increased from 12.3 percent to 14.2 percent. The remaining segments fluctuated or generally decreased over the same time frame. The upshot? Even though overall job losses were flat, that finding was driven by increasing losses in lower-income segments and decreasing losses in higher-income segments.

Percentage of Respondents Reporting Job Loss

On the other hand, the CFI’s surveys have consistently found how important relief programs have been to low- and moderate-income Americans ― these programs have resulted in disparate improvement in their sense of well-being, while higher-income groups have been less affected by them.

Profoundly unequal economic experiences have implications for how our country sets policy. There is a real risk that if policymakers are insulated from economic conditions across the country ― that is, if they and those around them are experiencing disparate improvement ― they could badly misjudge which policies are necessary. The solution, as always, is to strive for a deeper, more holistic understanding of the way Americans now live. The CFI’s surveys are a great way to further that understanding.

My colleagues at the CFI plan in the coming months to redesign the survey for the post-COVID era ― the new normal, as we’re calling it. When will that post-pandemic era finally arrive? If only we had the data to tell us that!

- The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia or the Federal Reserve System.