Racially Restrictive Covenants in the City of Philadelphia

Historical Context

A History of Housing Discrimination

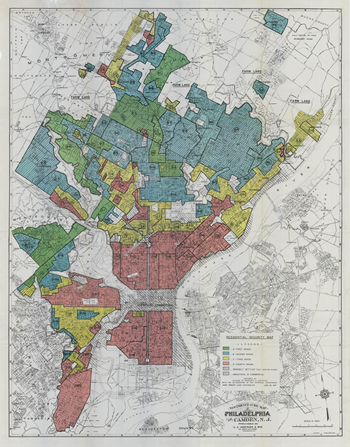

A 1937 Residential Security map for the city of

Philadelphia used by the Home Owners Loan

Corporation to make new loans to

homeowners at risk for default on their

mortgage. The color-coded maps assigned risk

grades to areas throughout the city, based in

part on neighborhood demographic

composition. Source: The Encyclopedia of

Greater Philadelphia.

In the early 20th century, a confluence of factors prompted a large and extended migration of Black individuals from southern states to northern cities, a movement referred to as the first Great Migration. From 1915 to 1940, hundreds of thousands of poor, rural Black Americans left the southeastern United States for northern cities, including Baltimore, Chicago, Detroit, New York, and Philadelphia.

The influx of Black migrants into northern cities magnified existing racial disparities and residential segregation patterns. Prior to the first Great Migration, Black people who lived in the northern states tended to work as servants and housekeepers for wealthy White families and often resided near their place of employment. White families lived along main streets, while Black residences were often clustered along side streets and back alleys.

During the early 20th century, Black neighborhoods grew larger and more homogeneous. Often, the housing stock available to Black people was in parts of the city that were no longer desirable to White people because of their proximity to industry or physically deteriorating housing.

A variety of tactics were used to prevent Black migrants from settling in predominantly White neighborhoods. Early methods of deterrence were both physical and economic. Violence against Black people was common in low-income neighborhoods, whereas home prices and imposing various fees and dues created an economic barrier in upper-income neighborhoods. The racially restrictive covenant (racial covenant) was another tool that early 20th century developers, home builders, and White homeowners used to prevent Black individuals from accessing parts of the residential real estate market.

Real estate advertisement for a

restricted development in the East

Falls neighborhood of northwest

Philadelphia. Source: Evening Public

Ledger, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

September 29, 1915.

Racial covenants were obligations inserted into property deeds that typically forbade persons not of Caucasian descent from occupying or owning the premises. The use of racial covenants accelerated rapidly through the 1910s and 1920s. By 1940, 80 percent of property in some cities (e.g., Chicago and Los Angeles) carried restrictive covenants. Within the city of Philadelphia, covenants were put into place to restrict the movement of Black individuals into new developments and predominantly White neighborhoods (Santucci, 2020).

During this time, courts could order Black families to vacate homes in White neighborhoods. This practice was legal until 1948, when the Supreme Court ruled that racial covenants could no longer be enforced in state courts. Despite the ruling, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) continued to refuse mortgage insurance to racially inclusive projects. FHA officials stated they had “no responsibility for a social policy …” (Rothstein, 2017). On February 15, 1950, the U.S. Solicitor General intervened to prevent FHA from using racial covenants as a precondition for mortgage insurance. The FHA continued to finance racially exclusive subdivision developments until 1962 when President John F. Kennedy issued an executive order prohibiting the use of federal funds to support racial discrimination in housing.

While much work has been done to document the existence of racial covenants throughout the country, little is known about their effects. This is beginning to change. A recent study presents evidence that racial covenants placed on properties during the 1940s had significant and persistent effects on home prices and Black spatial concentrations and homeownership rates in the Minneapolis area. Their results add to a growing body of economic research that finds long-lasting effects of redlining (Aaronson, Hartley, and Mazumder, 2021).

NOTE: The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia or the Federal Reserve System.